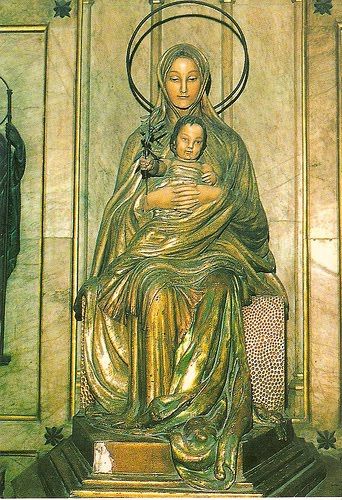

Our Lady of the Olives

Basilica of Our Lady of the Sea

Barcelona, Spain.

Our Lady of Olives is to be situated within the larger context of the biblical symbolism of the Olive tree. In the Bible, but also in patristic and medieval writings, the olive tree–together with the vine and wheat ears–was considered a symbol of heavenly blessings, prosperity and fecundity in times of peace.

The olive tree is also a symbol of spiritual excellence and distinction such as reconciliation with God, rectitude and innocence as well as fruitfulness of good works. This symbolism applied to Mary is a sign of faithful and loving dedication to the Lord but also a symbol of Mary’s strength, intercessory power and mercy. Originally borrowed from Sirach 24:19 (Vulgate, or v. 14) the expression oliva speciosa (fair olive tree) changes according to specific meanings: for example, oliva fecunda (fruitful olive), oliva pinguissima (fat, rich olive), oliva mitis (meek olive).

The use of this symbolism is widespread and multifaceted. We find sanctuaries of this title in this country and many others, for example, France, Italy and Spain. Here are some examples of the variety of meaning this symbolism has in Italy.

The medal of Our Lady of Olives is well-known throughout the Church and is of French origin. It takes its origin from a wooden statue of Our Lady which survived the destruction of the Church of Murat (Cantal, France) caused by lightning. This event occurred in 1493 and is the beginning of the devotion to Our Lady of the Olives. She is the protectress against lightning. By virtue of the Medallion of Our Lady of Olives, the persons who carry it are preserved from lightning wherever they may be during a storm.

The second privilege of the Medallion is to protect, in an unmistakable manner, women who are about to become mothers and to assist them in the hour of deliverance.

Those who are afflicted with sickness and who pray to the Divine Mother, are promptly relieved.

The Virgin was crowned June 18, 1881, by an apostolic brief given by Leo XIII on the tenth day of May 1878. Her feast day is celebrated as the first Sunday in September.

Prayer of Our Lady of the Olives

Kneeling at thy feet we pray thee, Virgin Mary, that through thine intercession there may be born a new generation which will unite all hearts and souls in the same faith and charity.

We pray thee, “Divine Olive of Peace,” to implore God that harmony may reign between nations, that true liberty be given to all people, that heresies and all bad doctrines condemned by the Pope Leo XIII may disappear.

We pray that all the treasures of the Divine Heart be showered upon all men and that we may be preserved from all harm.

Pray for us and save us. Amen.

Sources:

JMJ Book Company Catalog, p. 158

The Marian Library/International Marian Research Institute.

-

Our Lady of Olives PendantUS$ 79.00 – US$ 1,650.00

Our Lady of Olives PendantUS$ 79.00 – US$ 1,650.00 -

Miraculous Images of Our Lady: 100 Famous Catholic Portraits and StatuesUS$ 29.00

Miraculous Images of Our Lady: 100 Famous Catholic Portraits and StatuesUS$ 29.00 -

Our Lady of Olives Rosary

Our Lady of Olives Rosary

VIRGÓ SACRÁTA is a Christian mission-driven online resource and shop inspired from the beauty of Catholic faith, tradition, and arts. Our mission is to “Restore All Things to Christ!”, in continuing the legacy of Pope St. Pius X under the patronage of the Blessed Virgin Mary. “Who is she that cometh forth as the morning rising, fair as the moon, bright as the sun, terrible as an army set in battle array?” O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to Thee.