Every Catholic household should be provided with one or more blessed candles. These candles should be of pure bees’ wax. Other kinds, such as paraffin wax and electric candles will not answer the purpose of candles prescribed by the Church. Ask your local priest about blessing any candles you may have purchased from Virgo Sacrata, according to Traditional Roman Rite.

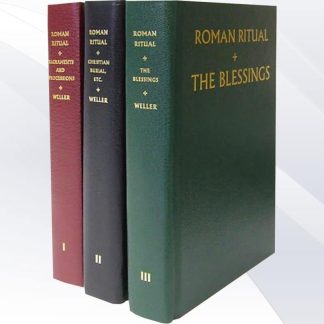

The best time to bless your candles would be the 2nd of February when the Church celebrates the festival of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This day has been chosen by the Church for a very important ceremony, the solemn blessing of candles, whence the day is often called Candlemas — the Mass of the candles. The prayers which are used in this blessing during the Mass are quaint and beautiful, and express well the mind of the Church and the symbolic meaning of the candles. These prayers are found inside the Traditional Latin Mass Missals that you should have on hand during the Mass. Or use prayers given below from the Roman Ritual Book of Blessings, which also contain prayers in Latin language.

Blessing of Candles

℣. Our help is in the name of the Lord.

℟. Who made heaven and earth.

℣. The Lord be with you.

℟. May He also be with you.

℣. Let us pray.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, bless ✞ these candles at our supplication. By the power of the holy ✞ cross, pour out upon them a heavenly blessing, O Lord, who gave them to human kind in order to repel the darkness. From this signing with the holy ✞ cross may they receive such blessing that, wherever they are set up or lighted, the princes of darkness may begin to tremble and depart, may flee in fear with all their ministers from such dwelling places, and may not dare again to disquiet or molest those who serve you, almighty God, who live and reign forever and ever.

℟. Amen.

They are sprinkled with holy water.

Blessing of Candles with Exorcism

℣. Our help is in the + name of the Lord.

℟. Who made heaven and earth.

℣. The Lord be with you.

℟. And with your spirit.

℣. O candles, I exorcise you in the name of God ✞ the Father Almighty, in the name of Jesus ✞ Christ his Son, our Lord, and in the name of the Holy ✞ Spirit. May God uproot and cast out from these objects, all power of the devil, all attacks of the unclean spirit, and all deceptions of Satan, so that they may bring health of mind and body to all who use them. We ask this through the power of our Lord Jesus Christ, who is coming to judge both the living and the dead and the world by fire.

℟. Amen.

℣. Let us pray.

Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, light of everlasting life, you have given us candles to dispel the darkness. We humbly implore you now to bless ✞ these candles at our lowly request, and hallow ✞ them by the light of your grace. By the power of the Holy ✞ Cross, endow them with a heavenly blessing. May the blessing they receive be so powerful that, wherever they are placed or lighted, the princes of darkness shall flee in fear, along with all their legions, and never more dare to disturb those who serve you, the almighty God. Let the entire building in which these candles are kept, be free from the power of the adversary, and be defended from the snares of the enemy. Grant we pray, that those who will use these candles may be protected from every assault of the evil spirit, and be safeguarded from all danger. Through Christ our Lord.

℟. Amen.

They are sprinkled with holy water.

Light a blessed candle when you sense an evil presence or manifestation in a certain place. The light from blessed candles symbolizes Jesus, the Light of the world; the presence of the Lord drives away all spirits of darkness. Lighting this candle, then praying for liberation is especially effective to purge a place especially a room, from infestation.

-

Mary Help of Christians – 100% Pure Beeswax Votive CandlesUS$ 33.00 – US$ 59.00

Mary Help of Christians – 100% Pure Beeswax Votive CandlesUS$ 33.00 – US$ 59.00 -

The Sacred Heart of Jesus Devotional Candle (100% Pure Beeswax)US$ 26.00

The Sacred Heart of Jesus Devotional Candle (100% Pure Beeswax)US$ 26.00 -

Three Days of Darkness Candle in Glass Container (100% Pure Beeswax)US$ 37.00

Three Days of Darkness Candle in Glass Container (100% Pure Beeswax)US$ 37.00 -

The Roman Ritual – 3 Volume SetUS$ 175.00

The Roman Ritual – 3 Volume SetUS$ 175.00 -

1962 Parish Ritual (Collectio Rituum)US$ 105.00

1962 Parish Ritual (Collectio Rituum)US$ 105.00 -

Candles In The Roman RiteUS$ 20.00

Candles In The Roman RiteUS$ 20.00

VIRGÓ SACRÁTA is a Christian mission-driven online resource and shop inspired from the beauty of Catholic faith, tradition, and arts. Our mission is to “Restore All Things to Christ!”, in continuing the legacy of Pope St. Pius X under the patronage of the Blessed Virgin Mary. “Who is she that cometh forth as the morning rising, fair as the moon, bright as the sun, terrible as an army set in battle array?” O Mary, conceived without sin, pray for us who have recourse to Thee.